Need for Speed: Indian Railways

Prologue

Indian Railways is among the top five rail operators in the world with a staggering $27 billion revenue, 1.5 million workforce and transports 8 billion passengers every year. Over its 170 year operational history, it enjoyed undisputed market share in public and freight transportation with its vast 68000 km network connecting every nook and corner of the country.

However, with the exponential rise in road infrastructure and the coverage of air transportation over the years, Indian Railways (IR) has been losing its market share to faster air and cheaper road transportations. IR is in the dire need for speed to remain competitive and sustainable in future. And to achieve the same, the LORG has laid down a massive modernisation masterplan and has been implementing the plan through exemplary innovation and engineering to solve some of the most challenging problems, at a scale perhaps no other rail operator in the world has ever attempted.

Original Photo by Sai Kiran Anagani on Unsplash, edited by Kiran Sripada

Original Photo by Sai Kiran Anagani on Unsplash, edited by Kiran Sripada

Indian Railways operates most trains at a maximum speed of 110 kmph. Despite having a rail network that accommodates faster movement of trains, IR could not increase the operational speeds due to the following challenges:

- Locomotives

- Rolling Stock

- Network capacity

- Level crossings and Trespassing

Problem 1: Locomotives

Indian trains are powered by a detachable locomotive. Until late 2000s, its fleet of locmotives were predominantly diesel-electric since a vast majority of its rail network was unelectrified. The diesel locos rated with a power of 2500-3000hp were capable to haul a passenger train with 18 coaches at 120 kmph. But their inability to decelerate and accelerate faster limited the average speeds of many passenger trains to 40-50 kmph and freight trains to 25 kmph. IR produced more diesel and electric locomotives with 3000 - 5000hp power to haul longer trains at greater speeds but acceleration woes and presence of unelectrified sections in the route led to nominal increase in the average speeds.

A fleet of high horsepower electric locomotives can haul 24 coach passenger trains at 160 kmph with a fraction of operational costs required for a fleet of equally efficient non-renewable diesel-electric locos. Operationalising a fleet of 1000s of electric locomotives is a multi-year, multi-billion paradigm shift in IR’s rail network, loco production, operation and maintenance, to be backed with huge volumes of (up)skilled personnel.

Despite the massive challenge, IR has embarked on this journey and has been comissioning electrified sections spanning 2400 km every year to become carbon-zero by 2030 with a fully electrified rail network. IR has invested heavily on research and development of the next generation of electric locomotives and produced units with power as high as 12000 hp. These locomotives are capable of running freight and passenger trains at 100 and 160 kmph respectively, effectively doubling their current average speeds.

Source: Posted on twitter by Chittaranjan Locomotive Works

Source: Posted on twitter by Chittaranjan Locomotive Works

Problem 2: Rolling Stock

The rolling stock of Indian trains (usually called as ICF coaches) has been designed to produce electricity required for HVAC systems on its own while in motion. This power generating equipment is located at the centre of the axles of the coach, which limits its operational speed to 110 kmph.

An existing alternative to the self-generation is the attachment of a diesel-powered electricity generator, used to be done to premium trains to increase their speeds to 130 kmph. Addition of such power generator coaches to a passenger train will mandate the replacement of two exisiting passenger coaches, leading to decrease in capacity and revenues. More importantly, the ICF coaches have a lower safety rating at higher speeds with their tendency to flip in the event of disaster.

Hence, the rolling stock needs a major tehcnological and safety upgrade, which came in the form of LHB coaches. IR has acquired the technology from the Linke Hofmann Busch in Germany to produce LHB coaces locally. LHB coaches can be hauled at speeds upto 200 kmph and are designed to be flip resistant. The power supply problem though is still unsolved. With its fleet of locomotives set to become all-electric, IR has developed Head-on Generation (HOG) technology to transform and supply the electricity from the over head power lines to the coaches through locomotives.

Source of images: Screenshots from videos posted by DFCCIL and TheRailZone

Source of images: Screenshots from videos posted by DFCCIL and TheRailZone

Problem 3: Network capacity

With the next generation of locomotives and rolling stock, passenger trains could be hauled at 160 kmph. The freight trains however can travel at most half the speed. Currently, passenger and freight trains travel together on the same tracks with provisions to loop the freight train out to make way for the faster passenger train, as they approach closer. The increase in the difference of speeds between passenger and freight trains:

- Leads to an exponential rise in the frequency of freight looping

- Limits the addition of new passenger and freight trains to the network

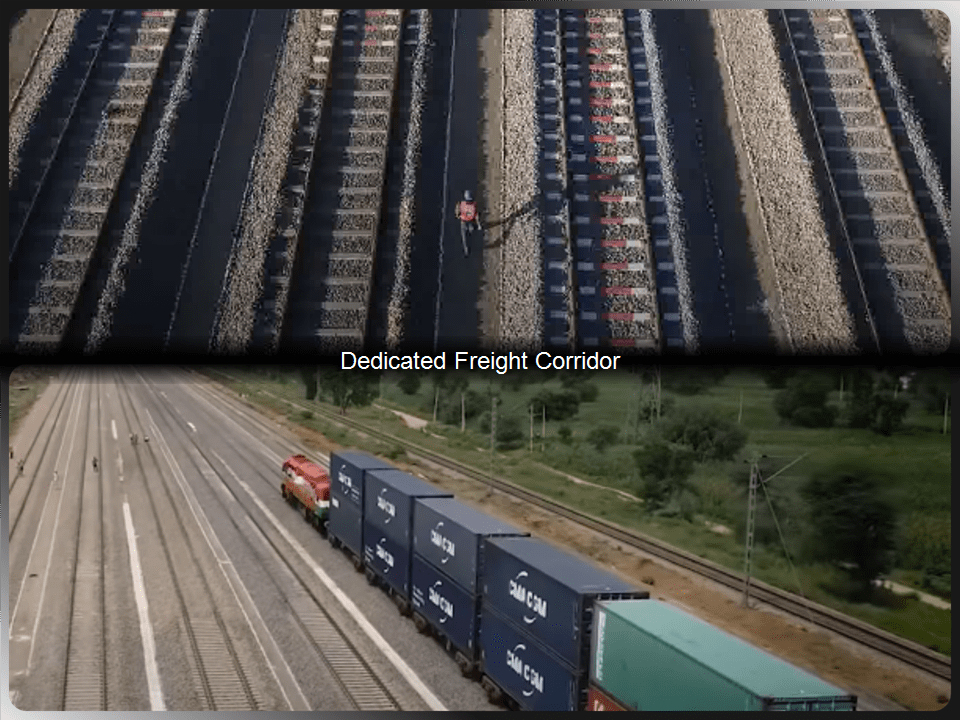

Hence, the freight and passenger trains cannot travel together, faster. IR has found that the problem can be solved by expanding its network by a fraction, which would still be the biggest rail infrastructure project ever. The golden quadrilateral connecting its four major hubs is a part of the rail network spanning 8000km. This quadrilateral is found to have 70% of the freight traffic movement. With enormous freight volume moving on a fraction of the network, IR has found a viable solution in constructing a dedicated freight corridor (DFC) along the golden quadrilateral and its diagonals.

The new DFC is designed to run freight trains at twice the speed with double the freight, effectively replacing four freight trains from existing network. With modern equipment like high-rise OHE and GPS-based signalling systems, the DFC is touted to be an engineering marvel and the longest freight corridor ever built.

With the new found additional capacity, the existing network is getting signalling upgrades to enable passenger train movement at 160 kmph with a headway of just 5-6 minutes.

Source of images: Screenshots from videos posted by DFCCIL

Source of images: Screenshots from videos posted by DFCCIL

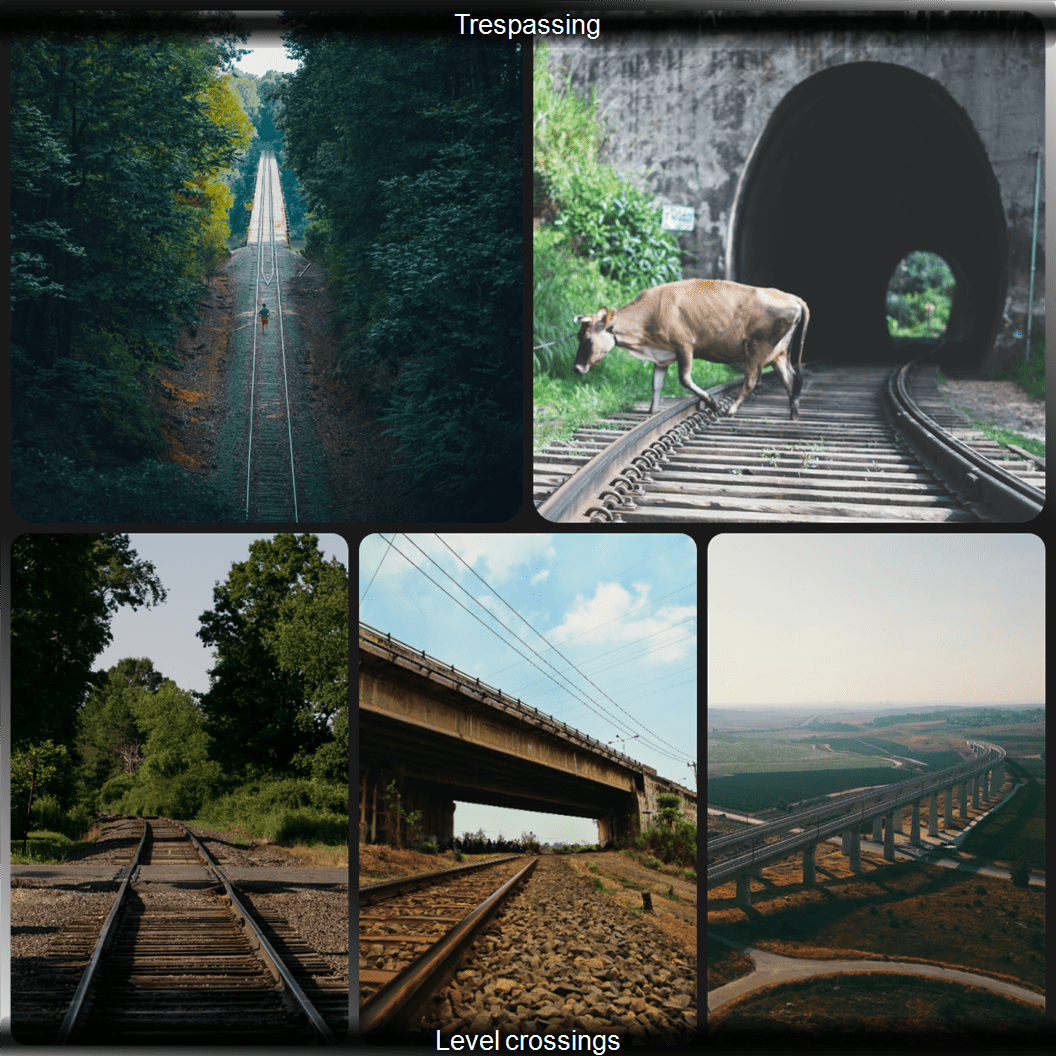

Problem 4: Level crossings and Trespassing

Now, there is space and support offered by the network to enable faster movement of trains equipped with new locomotives and rolling stock. But the last of the challenges in the quest for speed arises due to the inevitable rendezvous of rails with roads. These are called as level crossings where the movement on roads is temporarily obstructed to enable the free passage of oncoming trains. With the trains becoming faster and more frequent and due to the rapid growth of traffic on roads, level crossings will pose greater safety threats by becoming the sources of restricted and unrestricted human and animal trespassing on the tracks.

The only solution is to eliminate them once and for all by elevating either the rail or the road at the level crossing. There are 32000 level crossings across the network, a number so enormous that 30% of them were left unattended till 2018, let alone elevated. The level crossings are being replaced through the construction of road under bridges or road over bridges at a pace of 1200-1500 units per year since 2018. IR intends to fence the enitre golden quadrilateral in the near future and eventually its entire network from level crossings and trespassing.

Source of images: Unsplash

Source of images: Unsplash

Epilogue

Indian Railways is the centuries-old LORG with its legacy nearly undone by its tardiness and ageing operating procedure. Its turnaround in the last decade to become a modern government enterprise preparing to offer world-class service at humongous scale with ever growing safety record, commitment towards carbon footprint reduction and gender inclusivity, is nothing short of monumental and marks the return of the king of Indian transportation.